–

Love Colder Than Death (Wall pieces)

Installation Views

Video

Works

Press Release

An astute description of reality is an important language of realism. Spending time with things serves as entry point into their thingness, as well as the whirlpool of social situations they’re drenched in. Carefully observing, pacing your gaze becomes an inevitable privilege.

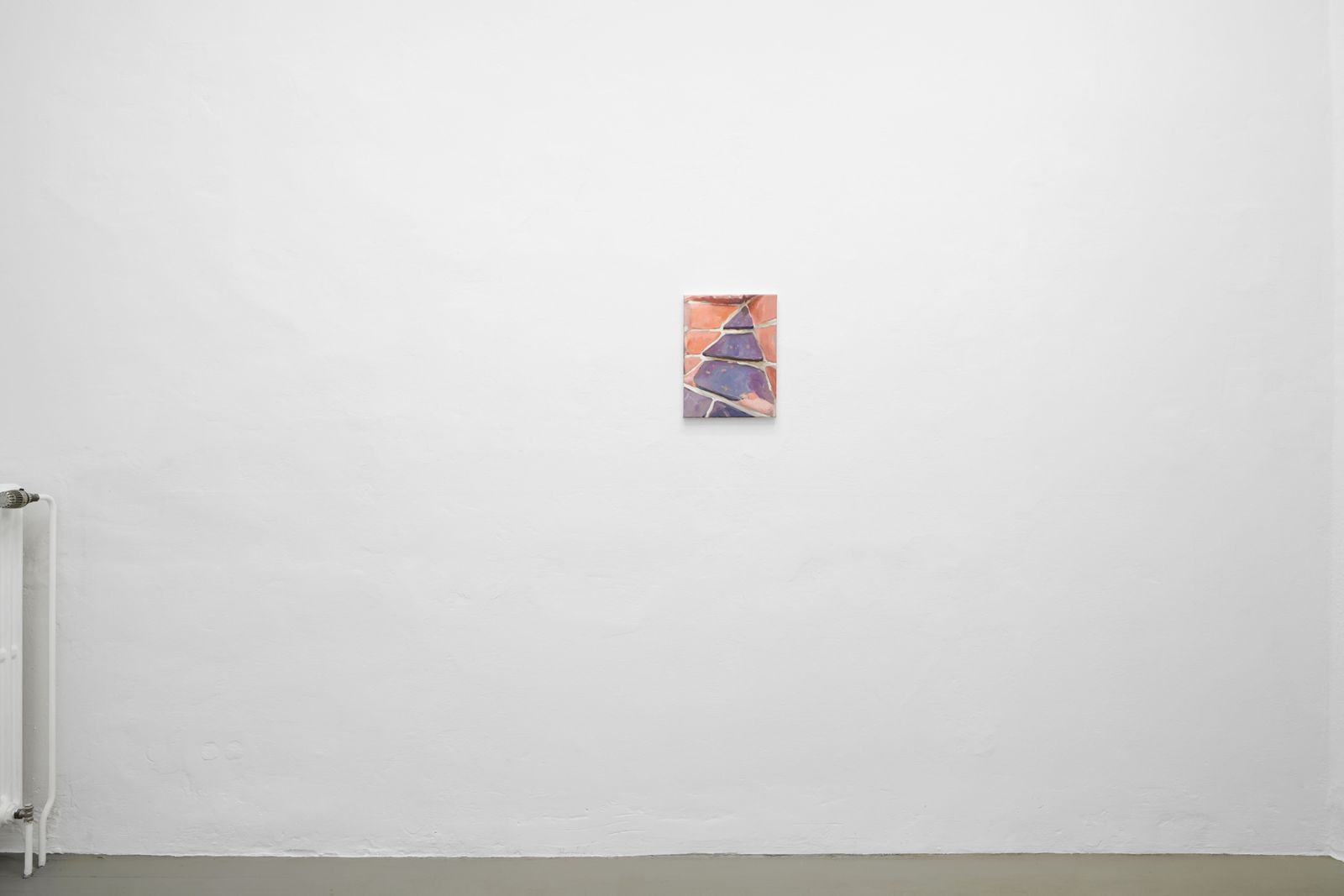

René Kemp worked on a new body of works titled “Wall Pieces”, which are presented within the framework of this exhibition. The works depict fragmented elements of several wall structures. Their size is a middle format, no bigger than 80 to 60 cm and they are all painted with oil on stretched canvas. The forms appearing atop of these canvases occupy their entirety, giving the image of a cropped detail and thus alluding to missing pieces of the wall that didn’t make it to the surface. They are based on impressions of walls around the city the artist came across in his daily commute through Cologne, sometimes elsewhere, operating in a rather diaristic manner. Some are based on photographs send by friends and colleagues. In their case a deliberately trivial modus operandi comes at play, to uncover something about the not-so-trivial quality of attention, which one could argue all forms of realism are ultimately based on. The artist works through the materials and visual traditions that come with the medium of painting, and yet he is perfectly aligned with the histories of conceptualism. Building on top of a productive system of images he ventures into a careful historical reflection.

Foucault wrote in „Manet and the Object of Painting“ (1971) that a wall operates like a canvas. It continues past the framed worldbuilding properties of the surface and bleeds through everything. But when walls entered paintings, they became, in Foucault’s eyes always, mere excuses for the medium to evolve and breath out. This fragmentary approach is perhaps more visible if one takes a closer look at the people in a lot of Manet’s works; in a standstill, running around, starring back at their viewers, being looked at, retreating. The Execution of Emperor Maximilian is a series of paintings by Manet, dating from 1867 to 1869 depicting a historical incident, which took place a year before in 1866: the execution by firing squad of Emperor Maximilian I of the short-lived Second Mexican Empire. Reacting to the incident Manet, who was an active supporter of the republican cause, produced three large oil paintings, a smaller oil sketch and a lithograph of the same subject. The final version was finished in 1869 but bares the date of Maximilian’s execution in 1866 alongside the artist’s signature. It is the only version of the work in this series depicting the execution scene in front of a large high wall. The wall structure stretches from one side of the canvas, all the way to the other, creating a clean horizon line and standing as a backdrop to the action.

Pacing artworks, allowing them the time to live their lives in full is the moral thing to do. If painting was able to voice opposition in a time of urgency, if is through reconditioning that she manages to escape contemporary obscurity. One of the walls of these “Wall Pieces” carries the inscription “love is colder than death”, which recalls the 1969 film with the same name, a crime love-trio drama by Rainer Werner Fassbinder about a pimp, a gangster, and a prostitute. There is an inherent irony in purposefully titling these works “Wall Pieces”, as if to render visible their status as failed communication devices or commodities, and emphasizing the alleged ultrabanality of a wall, its “worthiness” of depiction. As if they are, in the most literal sense of the word, pieces of a broken wall hanging from an unbroken one.

Haris Giannouras