Installation Views

Video

Works

Press Release

An arrow pierces the bare chest of the youth. The red coat draped loosely over his shoulders emphasizes the body’s contour. In his left hand, his arm bent and resting on his knee, his body turned slightly to the right, he holds another arrow. Unimpressed by his wounding, he gazes raptly into the distance. Agnolo Bronzino’s Saint Sebastian, circa 1528/29, is unharmed and immaculately beautiful, downright lovely-bewitching. In addition, other of the extremely numerous iconographic representations of the patron saint are more explicit in their display of pain and suffering, showing the body tied to a tree or column, pierced by a multitude of arrows. With the Renaissance, the saint is increasingly stylized as an icon of masculine beauty, sensuality, and lust.

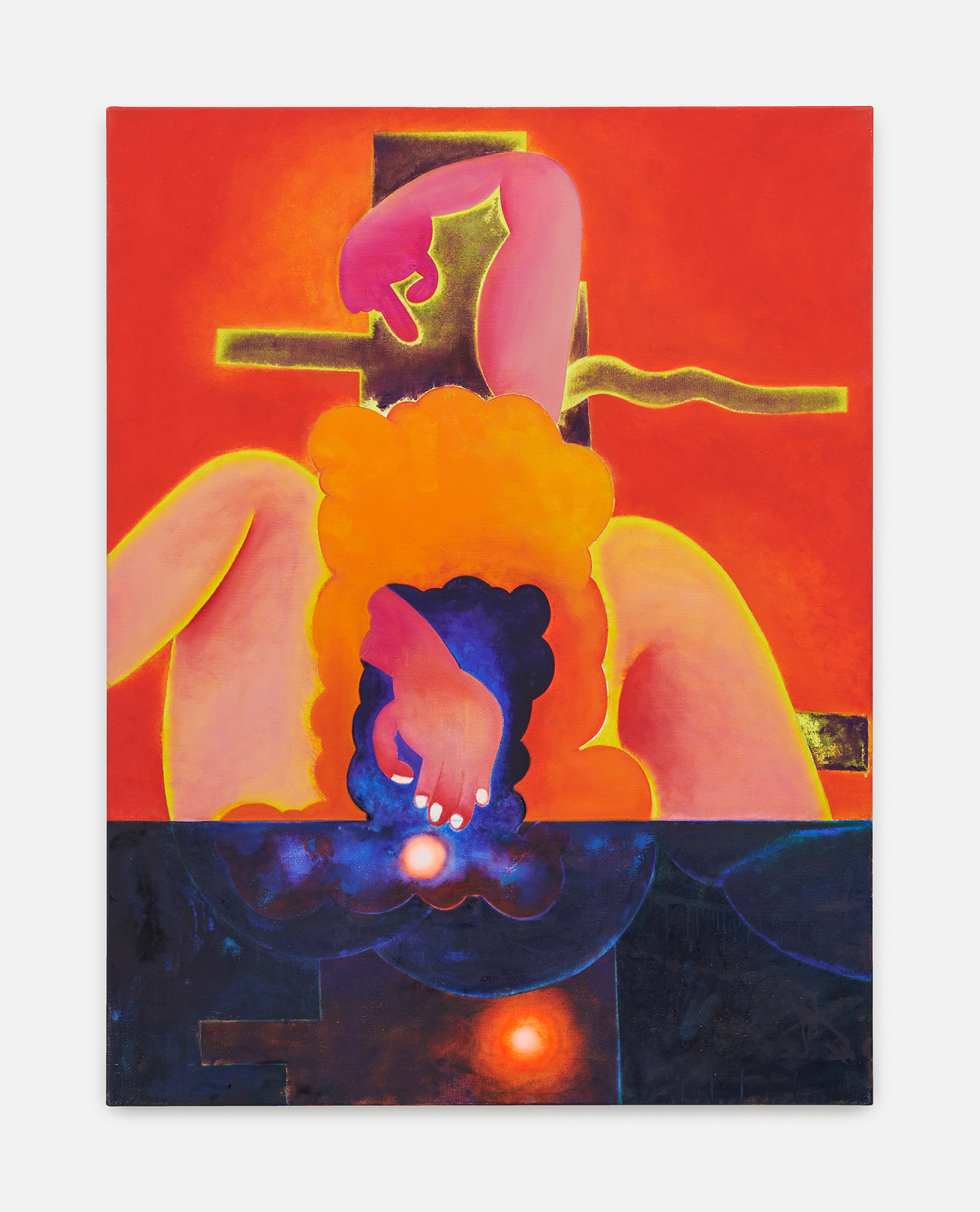

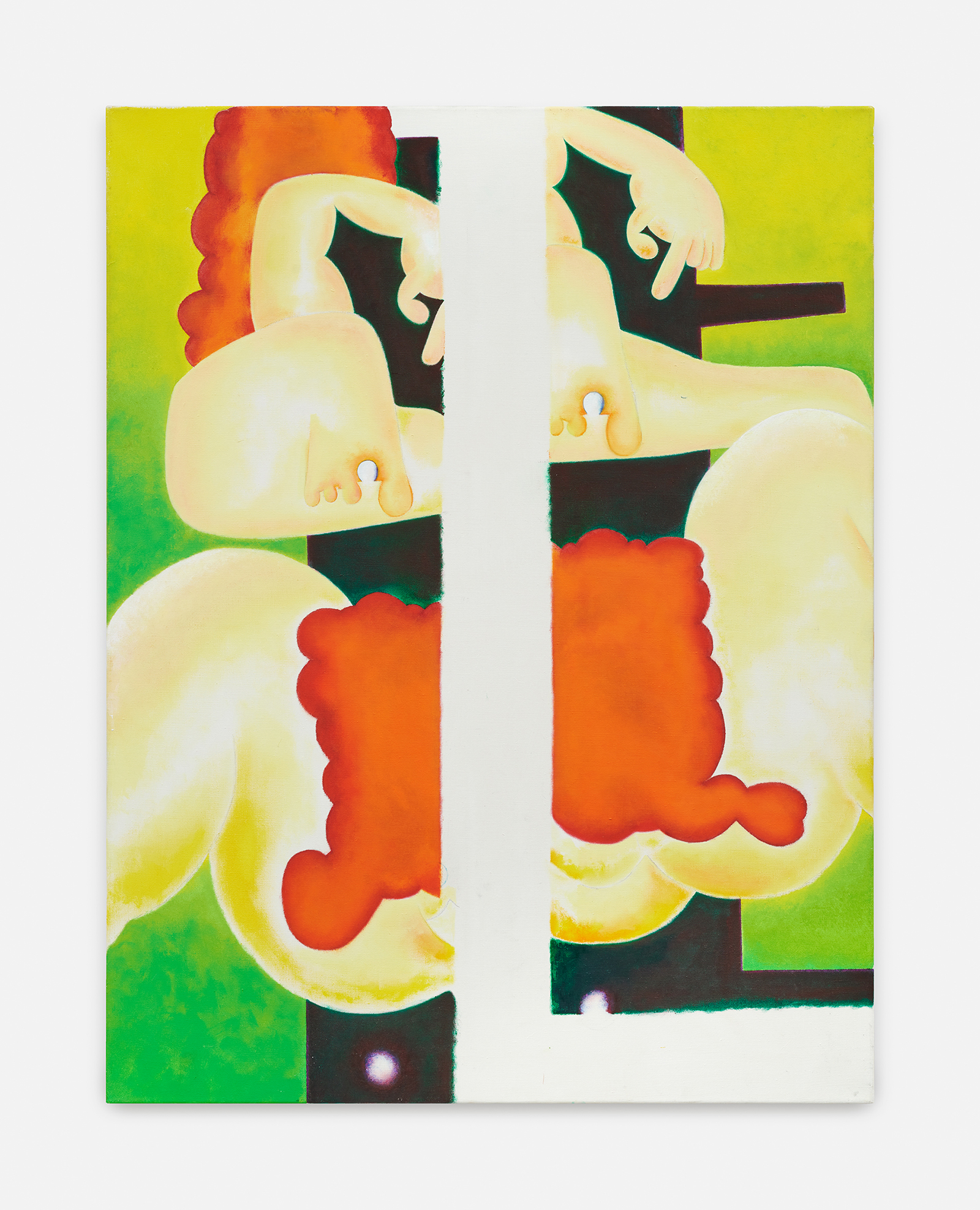

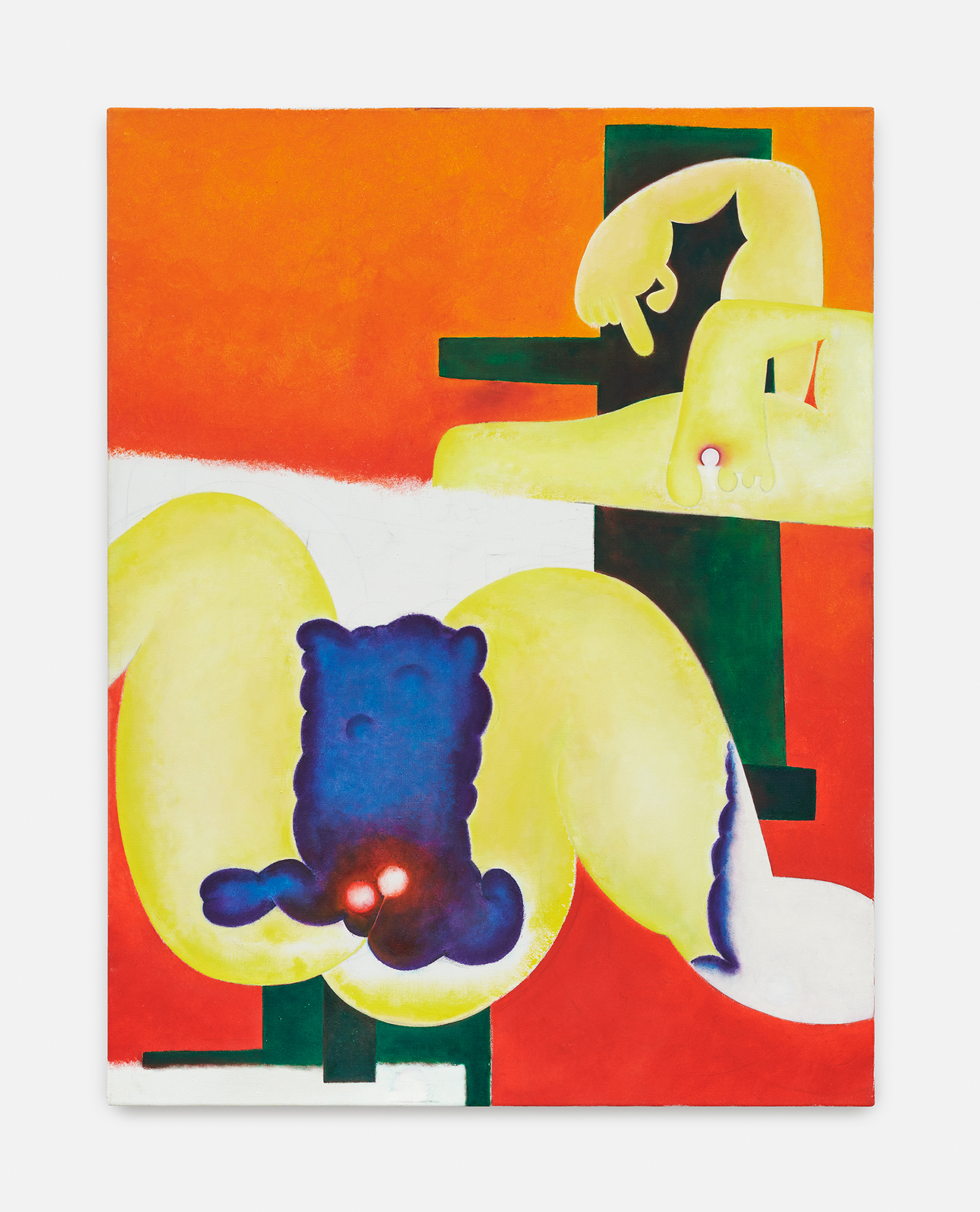

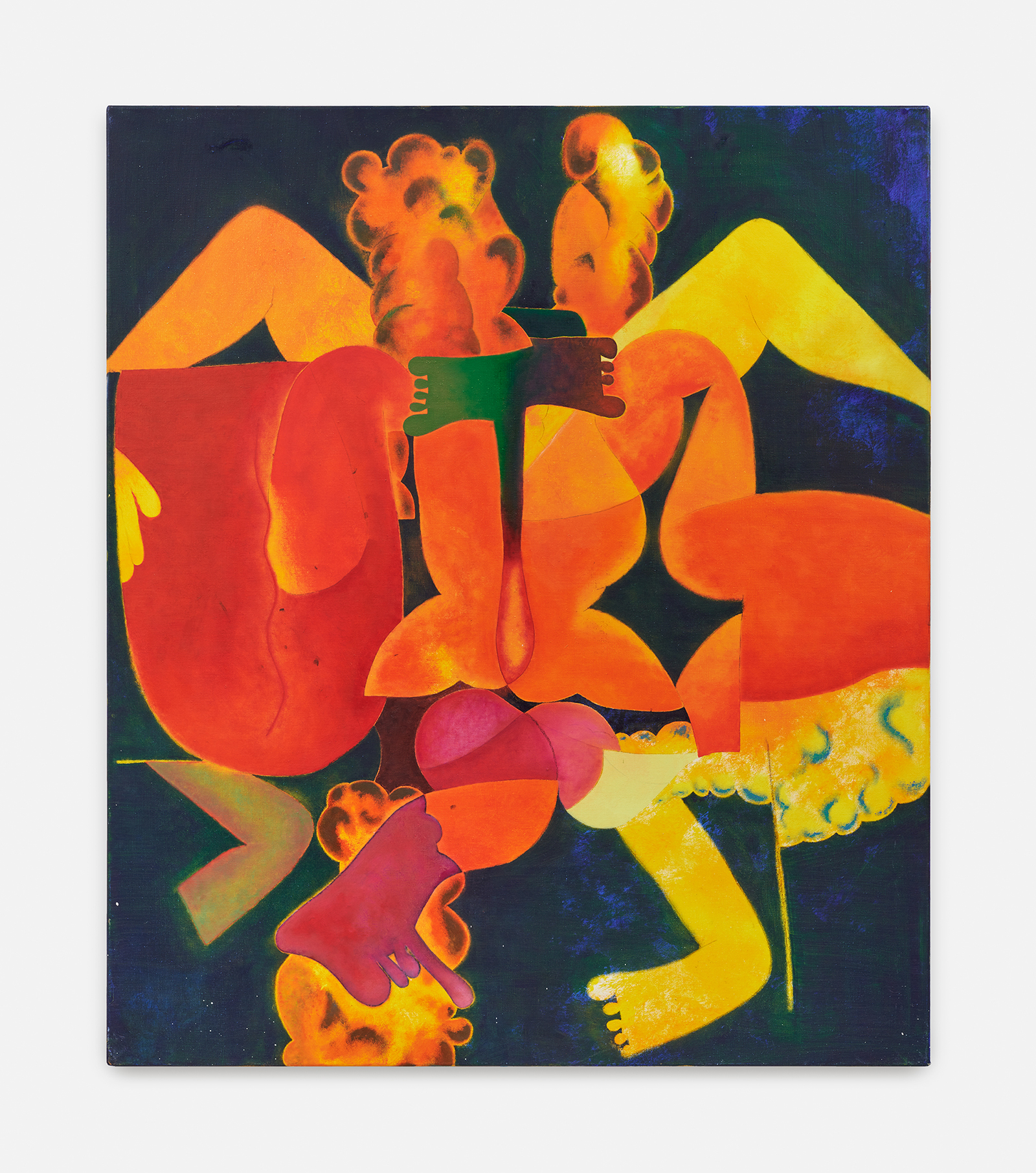

Bronzino’s painting, which “so prominently stages Sebastian’s arm with the arrow and formally offers it to the devout viewer for veneration at the lower edge of the picture” 1 serves Lutz Driessen as a starting point for his exploration of bodily states. For his first solo exhibition at Galerie Khoshbakht, new drawings and paintings have been created under the title living, which repeatedly take up Sebastian’s forearm and hand position as a pictorial element. The tenderly holding, touching gesture is joined by a pointing hand with an extended, perhaps exploratory index finger. Next to it, feet, thighs and other bulging outgrowths waft and wander, transgressing gender to dissolving it – oscillating between buttocks, testicles, breasts and vulva lips. The compositions are reminiscent of what Klaus Theweleit calls fragmentary bodies in his major work “Männerphantasien” (1977): The inability of one‘s own positioning beyond a body armor, when there are no longer hierarchical boundaries, and the associated fear of body dissolution, which Theweleit describes as the cause of the emergence of fascism, abuse of power, violence and war.

Some of the canvases worked on by drawing are sewn together like diptychs and display their seams like scars. Also central are the carved-out contours, which, in an attempt to separate the inside from the outside, rather emphasize their dissolution.

The lack of an outside through isolation can lead to the loss of subjective body perception, even to depersonalization, the detachment from the self. Didier Anzieu speaks here of the skin ego: “Just as the skin has a supporting function for the skeleton and the musculature, the skin ego serves to hold the psyche together.” 2. The skin is not only a protective covering, but also a surface of contact with the environment and thus an instance of self-assurance.

With the outbreak of the plague in Rome after 1348, Saint Sebastian gained new prominence: the idealized representation of the body as a welcome contrast to the vulnerable bodies battered by the pandemic and in decay. Sebastian, who survived the martyrdom of the arrow by a miracle of God, thus becomes “a promise that the faithful, even if they must die the black death, will be given a timeless, supernatural, immaculate body” 3.

A recurring motif in Driessen‘s pictorial composition is also the circle or the ellipse – as a hole or a gap, as an empty space, as an opening in the body, or shining sacrally as a halo. The question of the body’s demarcation from the outside world is transferred directly to the canvas: Driessen’s works point to something outside the picture plane – and outside the body.

Drawing from this extensive repertoire of forms, Driessen works through variations of repetition in order to get to the bottom of the essential: In their repetitive take-up of pictorial elements, the large-scale drawings might appear to be exercises or preliminary sketches of the paintings. On closer inspection, however, they expose in their sincerity that which is condensed – two-dimensionally, multiply applied and removed – in the paintings. In the end, what remains is what unites, there “where solid and contourless meet and mix, even and especially in decay” 4.

Miriam Bettin

Quotes freely translated from German editions:

1 Bastian Eclercy, „Agnolo Bronzino, Heiliger Sebastian, um 1528/29“, in: Bastian Eclercy (Ed.), Maniera. Pontormo, Bronzino und das Florenz der Medici, Munich 2016, p. 141-142.

2 Didier Anzieu, Haut-Ich, Berlin (6th ed.) 2016 (1st ed.: Frankfurt am Main 1985).

3 Daniela Bohde, „Ein Heiliger der Sodomiten? Das erotische Bild des Hl. Sebastian im Cinquecento“, in: Mechthild Fend, Marianne Koos (Ed.), Männlichkeit im Blick. Visuelle Inszenierungen in der Kunst seit der Frühen Neuzeit, Cologne 2004, p. 79-98.

4 Klaus Theweleit, Männerphantasien, Berlin (2nd ed.) 2020 (1st ed.: Frankfurt am Main / Basel 1977/78).