Installation Views

Video

Works

Press Release

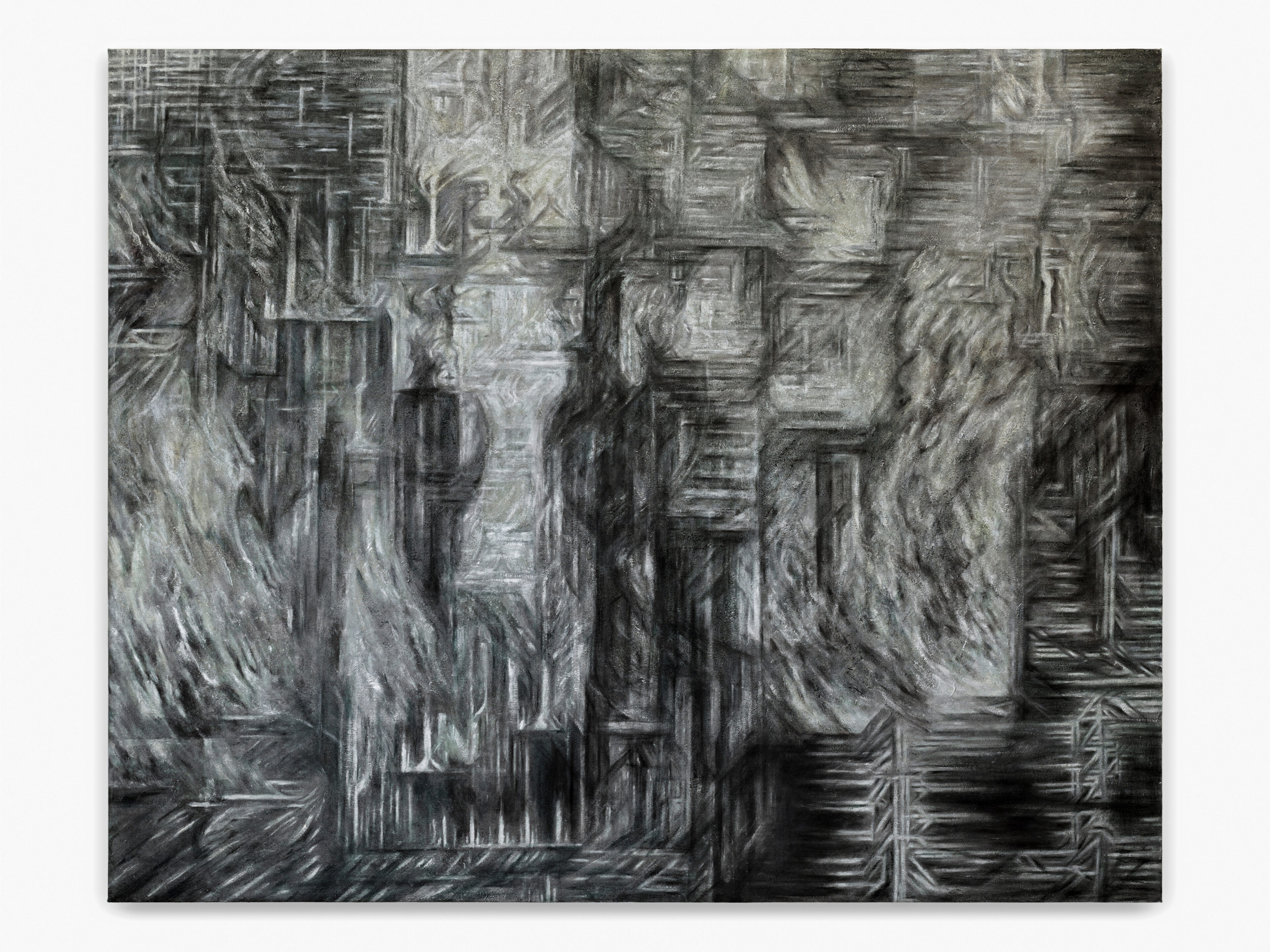

In the work of Raha Raissnia painting, film, photography, even the carousel slide, all share an isomorphic relationship. In that, if the image is able to be placed then it must also be able to move. For much of Raissnia’s career this has been most often found in her work with film.Collating and collaging multiple, different reel projectors and carousels into performances which—as she controls their mechanics—shred any understanding of a linear order, these filmic works by Raissnia slice through not only the history of cinema but also of the fuller world of image construction. In these works, as well as her paintings, there is favored a search within images whereby the path is cut-through, erased, written over, and constantly re-worked—better, re-formatted—to underscore a truth about images: they can never be caught or completely perceived. This inability to own or to possess incites a desire then, a mania that the artist entrusts in herself, that equates to an obsession with images.

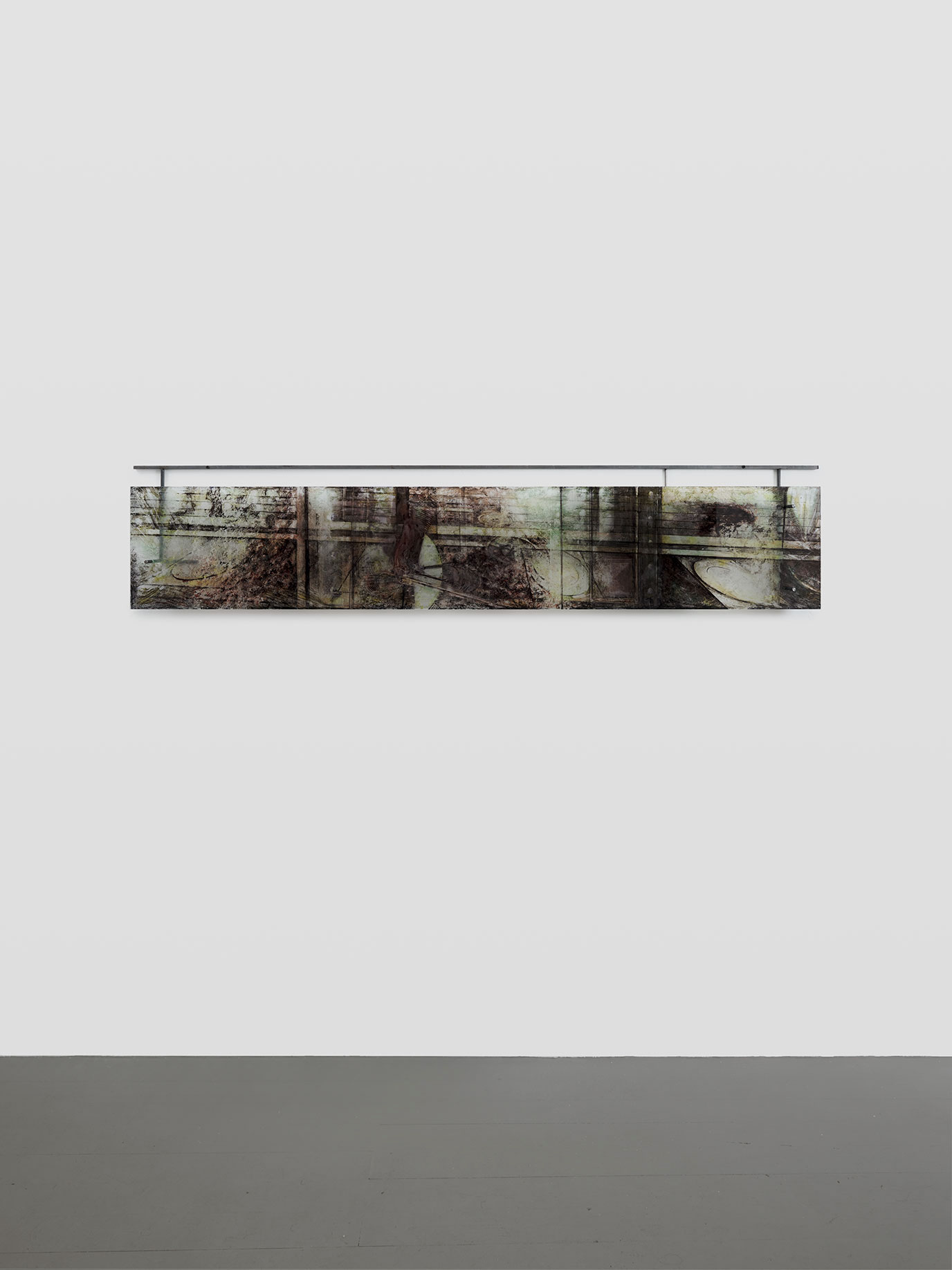

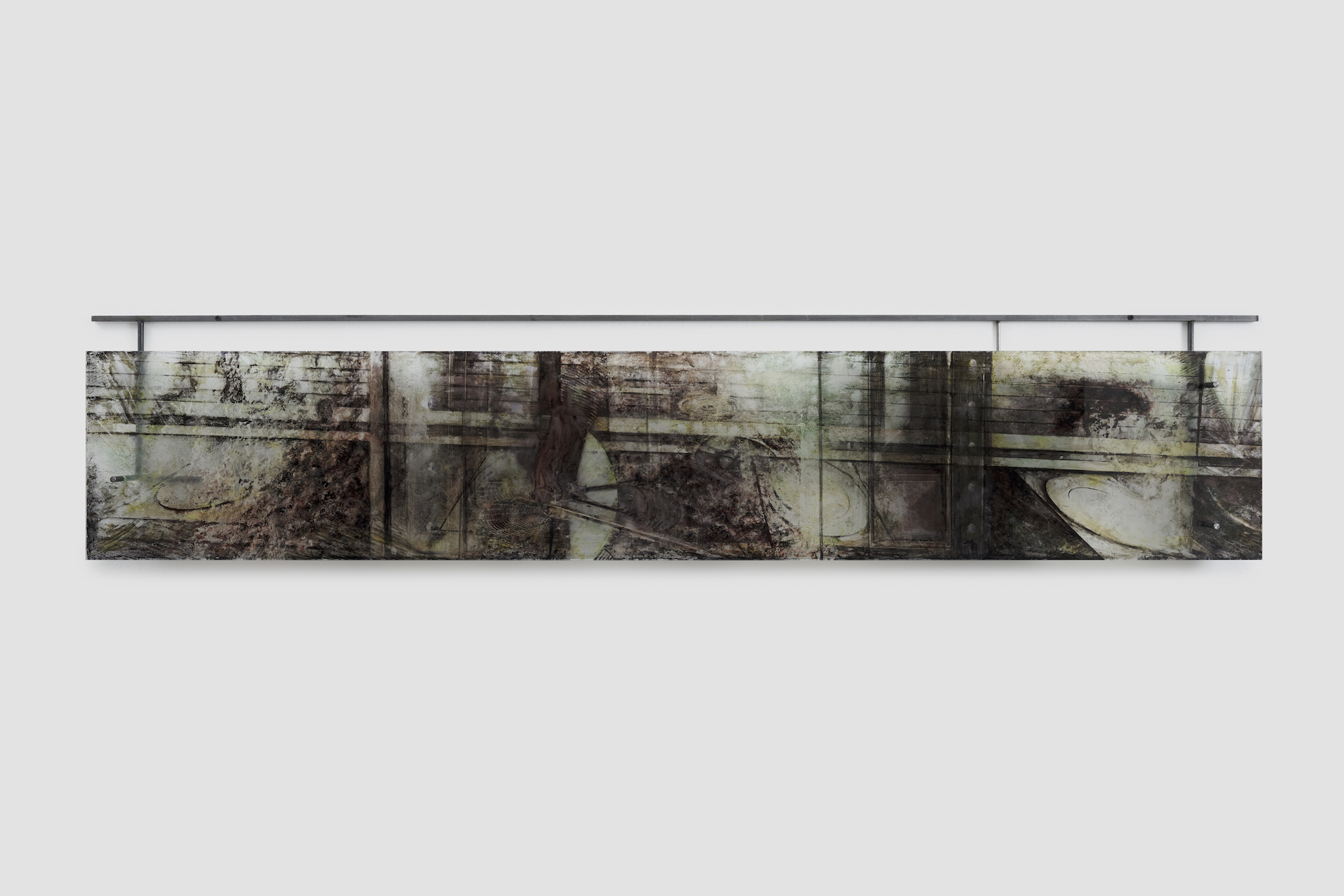

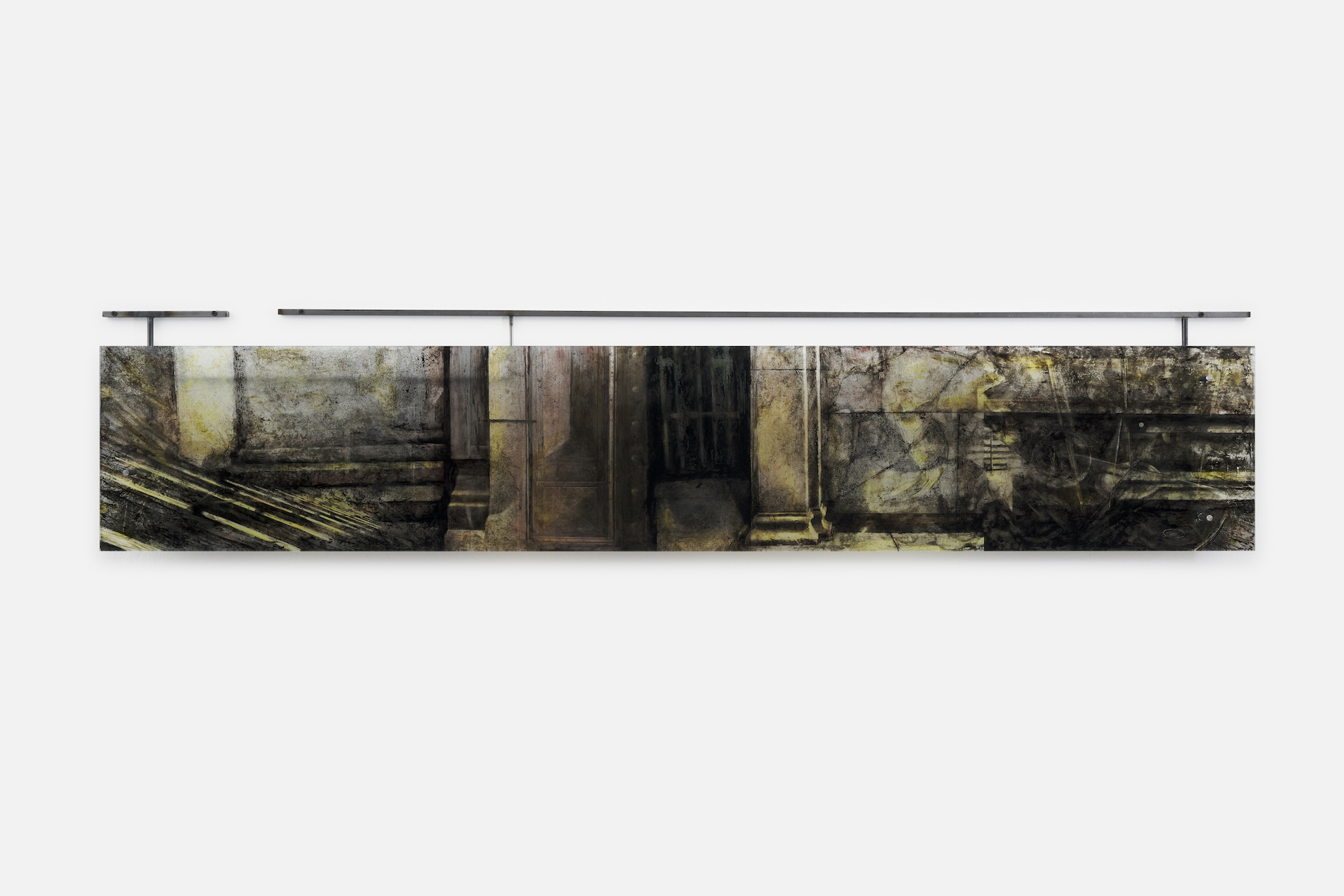

Having worked with the artist in the past and watched her create works for exhibitions or perform such filmic excavations, I have witnessed this manic obsession both in the work and in her practice. Often working deep into the night on a painting or meticulously laboring over different qualities of a slide, I was always in wonder to the manners in which she worked. Out of these intense bouts would come images and forms that made me think to cathedrals from the realm of H.P. Lovecraft. In other pictures, images of scarred landscapes or bodies would come to the fore, wherein these exposed entities demonstrated their own construction through equal compression and fragmentation. Another quality that can never be denied is their color. But it is not simply just color, as the insistent, repeated usage of high contrast blacks, whites, ochres and browns, colors that are more elemental than Earthly, turns them from being mere rudiment into sacrament. Here in this obsessive, methodical mode of working for Raissnia belies a mode of spirituality—devotion unto and absolution through images—that gives consciousness to the images and materials. Hinging upon this portrayal of spirituality and consciousness, in this exhibition the artist has produced works that are both entirely new to her practice but extend from a trajectory established in her films and paintings. By using glass to print, draw and paint on, the forms of cinema and painting collapse and coalesce onto one another that, while obfuscating their identity, makes their presence and activity in the work all the more observable.

This usage of glass is a curious one, as it almost seems like such an obvious choice for Raissnia. Therefore, questions such as “why now?,” ”why here?” occur to me as an observer ofher work. Is there reason in her choice to only now explore and develop this material in herpractice? To these questions I would hesitate to ascribe any one cause or meaning as to why this material finds its way into her practice at this point in her career, but from where I stand as a friend, critic, and historian, this new extension of her work feels perfectly timed in her practice. As a material, it is one that allows images and their projections to literally change and multiply in perspective over time. For Raissnia, there is a “doubling of the image” at play here that is similar to her double projections she uses in the films. 1 Shadows, light, images, each of these move in relationship to the viewer and where they find themselves in front of the work. More, by UV-printing onto the glass and then painting, inscribing and drawing onto the panels by hand, the different histories and practices of Raissnia coalesce into the glass works—creating a sense of double history then as well—which equally folds into themselves the history of glass as a material. Referring to a comment made by filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky, Raissnia recalls that glass, specifically stained glass, “was the first form of cinema, that is light filtering through imagery, the same as film.” 2

While the application of stained glass—most commonly recalled in High Gothic and Rayonnant architecture—is often the first direction the mind of the visitor travels when thinking around the material. It is much more curious and inviting to consider a more regional—not to mention spiritual—understanding of glass and its history as it was in Cologne, in 1914, that Bruno Taut’s first prototype for a glass pavilion was created. This pavilion was Taut’s physical illumination of his belief in Glasarchitektur. The belief in glass architecture, one which stemmed from Taut’s correspondence with and publication of the Berlin poet Paul Scheerbart, was one in which a new humanism and culture could be created. 3 Glass, specifically colored glass, was to be placed everywhere in this new architecture, so as to break down the forms of closed rooms and have transparency, light, and color—forms of the spirit—infiltrate into people’s homes and lives. However, being a part of the modernist project, the aspirations placed upon glass—for a new transparency onto life, or by bringing nature onto the hearth of the individual—shortly turned opaque and darkened. The glass facades of modern architecture, which sheath and house the companies of finance and industry, quickly become materials of management: portraying transparency while becoming barricade.

In Raissnia’s work, this material and historical complexity of glass come together in a shifting, uncertain force. The images printed upon and contained in the glass have no locality. Like a reel of film they are in constant movement. Similar to her paintings and drawings, an inscription and marking of place is described—be it a broken terrain or entity in decomposition—but no marking for time is given. The work of Raissnia remarks upon this paradox of images as they exist in a stasis of history but by a pathos separated from both the image and the artist they continually change and move towards a direction of increasing complexity and illegibility.

Alan Longino

1 In conversation with the artist, August 10, 2023.

2 ibid.

3 Paul Scheerbart (b. 1863 – d. 1915) was a poet and illustrator whose book Glasarchitektur (1914) became highly influential amongst architects from Walter Gröpius, Mies van der Rohe, to Frank Lloyd Wright (who in 1928 write on iridescent buildings and the benefits of a glass city). Like Taut’s pavilion, much of the writing and conceptualizing by Scheerbart on glass architecture is incomplete or amateur. Scheerbart’s unfulfilled propositions on glass underscore a belief that glass, while used here in aspiration for a new cultural revolution, could just as well be used as a new medium for the grotesque and ugly in the individual. If glass had the ability to bring transparency into the realm of the human, then then human could equally react against such natures.